Preamble

I am going to write about 2 competing priorities in training for the fitness competitor (i.e. CrossFit, Hyrox, IF3, etc.). Namely, training to compete versus training to improve your physiology.

But first…

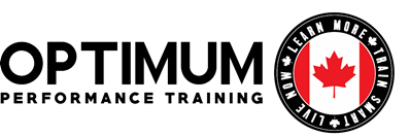

I see this problem and many other problems along the spectrum of hardware versus software focus to a training objective, a training session or the overall training plan. The hardware and the software are by no means distinct from one another, they are inextricably linked and work together as a functional unit.

I do believe I may be a bit too reductionist here in my approach. But, I also think this is a good starting point for analysis in many cases. This is not the end of the analysis, it’s the beginning.

I plan to cover this topic in much greater detail at a later date, but for now I will let ChatGPT provide you with a good definition of these words in the context of computer science.

“What is hardware in the context of computer science?

In computer science, hardware refers to the physical components of a computer system, such as the processor, memory (RAM), storage devices (hard drives, SSDs), input/output devices (keyboard, mouse, monitor), and other peripheral devices like printers or scanners. These components work together to execute instructions, process data, and interact with users.

What is software in the context of computer science?

In computer science, software refers to the programs, applications, and data that instruct the hardware how to perform specific tasks. It encompasses everything that isn’t a physical component of the computer system, including operating systems, device drivers, utilities, applications, and user-generated content. Software provides the instructions and functionality that enable users to interact with and utilize the capabilities of the hardware.

What is the difference between software and hardware in the context of computer science?

In computer science, hardware refers to the physical components of a computer system, such as the processor, memory, storage devices, and input/output devices. Software, on the other hand, refers to the programs, applications, and data that instruct the hardware how to perform specific tasks. In essence, hardware is the tangible, physical part of a computer system, while software is the intangible set of instructions and data that control and manipulate the hardware to carry out desired functions.”

Image: My 1st attempt to visualize the concept. Feedback welcome!

Using the framing of software and hardware, let’s continue on with today’s example – training to compete versus training to improve your physiology.

Very quickly, what I mean by training to compete is trying to be more specific with the training scenarios in an attempt to improve performance on game day. What I mean by training for physiology is designing the training with the explicit purpose to improve a certain physical marker, without direct reference to any particular competition. Not to say it won’t have a positive impact on performance, just that it would be indirect.

Intentions Matter

A simple example of this could be something like this:

Scenario 1:

Athlete performs 5 consecutive max effort Vertical Jump every min x 5 mins

—goal is to improve the rate of force development of the lower body in an attempt to improve the athlete’s ability to move a barbell (i.e. a clean and jerk)

—this is mainly a “physiology” intention, very little context with regards to a sport like CrossFit

Scenario 2:

Athlete performs 5 touch n go Power Clean and Overhead @ 50% RM every min x 5 mins

—goal is to improve work capacity/endurance, mainly with this specific movement

—this has more relevance to the sport, so more context, but still has an “improve a characteristic” feel to it – maybe a middle ground

Scenario 3:

Athlete performs 30 Clean and Jerks @ 135lb/95lb as fast as possible

—goal is to test the athlete in the context of the sport and to gain insights on how to proceed

—this is purely “competition” intention, not just about improve a specific quality, you want to see some data for a relevant test.

Work:Rest

Let’s unpack this concept a little more, and let’s focus on something different than the above examples.

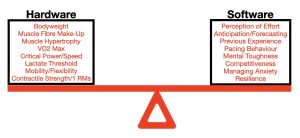

CrossFit style tests are very often characterized as work:rest formats, this is especially true the less able you are.

To try to avoid some confusion, I will provide an example of what I mean by work: rest formats.

Anyone familiar with CrossFit would know that CrossFit definitely incorporates plenty of interval designs in its training and in the testing at its various competitions. The design generally involves a couple movements of various numbers of repetitions or duration, followed by a period of rest. I am not talking about this. I’m talking about what goes on within the actual work interval itself.

Let’s say you have an event such as:

For Time: 15 Ring Muscle-up, 1k Row, 5 Cleans (Heavy)

Let’s say this event takes the fittest person in the world 5 minutes to complete. What percentage of this 5 minutes is spent resting? I would say very little, but it’s not zero.

Let’s say this event takes a high-level CrossFit athlete 6 minutes to complete. What percentage of this 6 minutes spent resting? A significant increase from the fittest person.

Let’s say a relative beginner to CrossFit takes 15 minutes to complete this. What percentage of this 10 minutes is spent resting? In this scenario, well, over half the time is spent resting.

So, when you look at an event like this, look a little deeper at how it’s actually performed. A graph of work output is not as it would appear during 400m Run (see graphics below). OK, I hope I’ve got my point across with regards to what I mean by work: rest within a work interval.

For many individuals, regardless of the duration of this event, it is going to be made up of bouts of work, followed by periods of rest until all five rounds of work are completed.

Hypothetical Pacing For 15 Ring Muscle-up, 1k Row, 5 Cleans (Heavy)

Hypothetical Pacing For A 400m Run

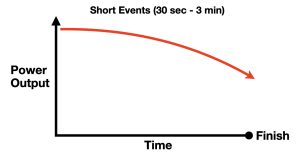

Short Work Is Easier Work

To paraphrase Philip Skiba, 30 seconds of work feels easier because it is easier. It’s easier to perform and it’s easier to recover from, all things being equal.

If you’re having to engage in an activity, say rowing for a period of time at your 2k PR pace. In all likelihood, its going to feel easier, and it’s going to be easier, to perform this:

20 Sets:

30 second Row @ 2k PR Pace

30 second Rest

Than it will be to perform this:

10 Sets:

60 second Row @ 2k PR Pace

60 second Rest

And this will be harder still:

5 Sets:

120 second Row @ 2k PR Pace

120 second Rest

All this to say, it makes sense when you watch individuals competing in CrossFit really try to optimally manage the duration of their efforts quite well. If they get the duration right (not too long), then they can also optimize the rest periods (also not being too long). Clearly, all of this is relevant to the level of the individuals ability. So, please keep this in mind as you move through this article.

The reason CrossFit competitors behave in this manner should make intuitive sense. If you’re able to go fast and it feels a bit easier to do so one way (short work/short rest) versus another (longer work/longer rest) then that is a good decision.

…But Longer Intervals Are Better (For What)?

Now, on the other end of the spectrum (training physiology), it is quite well understood in the exercise physiology literature that the greatest improvements in “work capacity” will generally come from performing bouts of work lasting 4 to 6 minutes (paces or power outputs close to and greater than Critical Power) and performing a few sets. Likely doing this 2+ times per week. This research is done with mono-structural movements in mind (i.e. run, row, ski, swim, bike, etc.), but that does not negate the fact that it’s true.

You are likely going to become a better endurance runner if you do 1K repeats at your 5K pace or faster than if you do the same pace, but in shorter intervals per set.

For example, for gains in physiology this is likely better:

5 Sets:

1k Run @ slightly faster than 5k Pace

2 Min Walk

Than this:

10 Sets:

500m Run @ slightly faster than 5k Pace

1 Min Walk

From that you could extrapolate to:

This:

Every 2 Min x 5 Sets:

30 unbroken Wall Balls

Being better than this (in terms of gains in physiology):

Every Min x 10 Min:

15 unbroken Wall Balls

Don’t Get It Twisted

One thing you should note from the examples I have provided above is the minimal requirement in terms of pacing. The work intensities are set. It is just a matter of performing the work and recovering between sets. Which means, the training designs are maybe not optimal for transfer to competition performance IMO. They may be optimal from improving performance with those specific modalities in that context, but competition performance in a sport like CrossFit is all about managing your effort in real time (current fatigue) and anticipating what is to come (future fatigue). Meaning, pacing.

Just because you are getting better at this:

EMOM x 20 Min:

1 – 13/10 cal Row

2 – 10 Bar Facing Burpees

Does not necessarily mean you will be getting better at this:

10 Rounds For Time:

13/10 cal Row

10 Bar Facing Burpees

What I’m trying to explain here is that you have to understand the intention of the design. Is the intention to help the person understand how to perform within the sport (The Software)? Or is the intention to help the person improve some metric of physiology in an effort to improve their performance in the sport (The Hardware)? Both are valid, but you need to know which one you’re focusing on. Also, this isn’t an either or, think of it more on a spectrum.

So what we have here is an understanding that shorter bouts of work feel easier, and are indeed generally easier to recover from. Therefore, it makes the most sense for individuals to pace unknown events in competition of significant duration (i.e. typically lasting 5 min+), in such a manner. This will hopefully maximize their consistency throughout the event.

But, on the other hand, there is plenty of research to show that longer durations of “high intensity“ work (read – unsustainable) are likely better able to improve an individuals work capacity.

The coach must find the optimal balance of providing contextual experience in which the individual athlete will be able to carry with them into competition, and feel that experience was valuable and worthwhile to their performance (The Software). On of the other hand, the coach must also ensure they are working to improve the individuals actual physiology so that they can come back as a better version of themselves when it is game time (The Hardware).

It is about attempting to balance their competition readiness with their individual needs. You need to be working on both at all times. How much you work on either will depend on who you are working with.

–Michael