Many years ago when I first began designing training programs for individuals I often would write percentages for effort. Such as 85 to 90% effort. Years before that even, I believe I would even use a percentage and then state something about “aerobic“. Prescribing something like, 80% aerobic. All that to say, I didn’t know what I was doing. I believe my intentions were good, but my actions weren’t.

For Example:

5 Sets: 1,000m Row @ 80% Aerobic, Rest Half Work Time

Repeatability is the word I was aiming for. This is true for many reasons, mostly, because it is a relatively clear way to communicate. You’re asking for a behaviour to occur, you’re not asking for some abstract performance metric like “80% aerobic”.

So what’s a good definition for repeatability in terms of fitness?

Maybe it’s… the ability to reliably and predictably perform the same task to the required standard over and over.

To continue, repeatability is the word you are most often looking to use. Not to be confused with the word sustainable. These two terms have lots of overlap, but they are vastly different.

Many times you will hear the word “sustainable” used. “Try to hold a sustainable pace”, or “it felt pretty sustainable”, or “it was a sustainable effort”.

For Example:

10 Sets @ Sustainable Pace/Effort:

500m Row

2 min Rest

—aim for around 2k pace

When, in fact, what the athlete is engaged in here is not “sustainable” when it comes to exercise physiology. As a matter of semantics, this doesn’t really matter because you can kind of deduce what the individual is saying or what you the coach are asking for. As long as Coach and athlete are on the same page, everything is good.

However, if you are trying to be as accurate as possible in your language, it does matter.

Most of the designs you are writing for individuals, or you yourself are engaged in are not “sustainable” for two main reasons.

Reason Number 1

The modalities utilized within the work interval will NOT allow sustainability to be achieved. Never.

Reason Number 2

You are having to take a rest between sets (or maybe even within the work set itself) in order to finish the training session. If rest is a REQUIRED aspect of the training intervals, then sustainability is likely not achievable.

When I am using the word sustainable in here, I am referring to the metabolic rate (oxygen intake, substrate utilization, energy production, etc) associated with the activity. Sustainable is not just one point in time, it does vary in degree, ease of attainment and maintenance over time.

Back to example listed above:

For this I have a particular person in mind that I watched perform the session.

10 sets:

500m Row @ 2k PR Pace

2 Min Rest

Each set was effectively performed at the same pace (repeatable).

Each set became progressively harder and harder than the last (intra and inter set increases in RPE = unsustainble).

If the 2 minute rest interval were not present, the individual could not complete this design. If we decreased the rest interval from 2 minutes down to 90 seconds, repeatability may become overly stressed and may not doable any longer. Repeatability not occurring is typically proceeded by near max levels of perception of effort (approaching 10/10).

If we shorten the rest period another 30 seconds down to only 1 minute, they would likely be unable to finish all 10 sets.

They would end up reaching task failure for one reason and one reason only, rowing at their 2K PR pace is unsustainable.

Moving on…

Why do you even want to achieve Repeatability? What for?

Quickly, observing repeatability in an individuals performance indicates an ability to adequately recover from a preceding bout of work. This also indicates that the previous bout(s) of work was not so excessive so as to become non-repeatable. Basically, it means the athlete is not being overly stressed (potentially excessive).

If you agree with the above framing, then you are agreeing that “Intensity” is a variable to be manipulated and managed, not something to always be pushed to its maximum.

This is something many individual struggle with in training. Even when I write that I want a repeatable effort and that I also want to be a high effort (7-9 RPE), very often it goes beyond the high effort and approaches a maximum effort (10 RPE).

Now, all in all, that’s not really a bad thing. Having individuals willing and able to push themselves that hard is indeed a good thing. Having a very high “willingness to act“ is paramount to performance. But, sometimes that’s not the best way to go about it. Sometimes, you’re stressing yourself too much.

That said, you need to know the individual you are designing the training for if you’re going to ask and require that level of effort from them. We will cover that a bit more later.

3 ways I try go about accomplishing “repeatability” in my training designs.

Number 1 – Communication

Utilize knowledge of how the “Intensity” of activity manifests itself in the individual, how they will experience that and what the predictable effects on their performance will be. Knowledge of exercise physiology would be required for a more complete understanding.

Whatever language you decide to use to communicate the prescribed intensity and/or effort you are looking for… it needs to be simple, it needs to be understood and it needs to be consistent in application.

Typically, I use a hierarchy something like this:

⏺️Easy Effort/Relaxed/Not Hard/Low Breathing Rate

⏺️Moderate Effort/Kind of Hard/Getting Harder/Breathing Higher But Stable

⏺️High Effort/Very Hard/High And Increasing Breathing Rate

⏺️ALL OUT Effort/Maximal Pace

If you are wanting an easy effort, you need to communicate that in some way. Conversely, it would are wanting maximum pace/effort you need to ensure the individual knows that.

As with all forms of communication, there are limitations. Many times when I’m asking for an easy effort from an individual, they are indeed not giving an easy effort. They are often going a bit too fast. Sometimes I see people going a bit too slowly, but that’s definitely less common.

Conversely, many times when I’m asking for a “high effort“ they get this right. You will always have some people that under do it or overdo it, but that’s just the way people are. That’s also not to say that this type of information is irrelevant, because it most certainly is not.

As you increase the intensity prescription of the task/set of tasks, you reduce the likelihood that repeatability will be possible.

It is still possible, but it is harder for the athlete to accomplish.

Repeatability occurs on a spectrum.

Minimum————————————Maximum

As the intensity expectation increases (ie High Effort vs ALL OUT Effort) the Coach will have to adjust the designs accordingly by shortening the work bout duration and/or increasing the rest duration and/or adjusting the number of work sets if repeatability is indeed the goal.

Once you push the athlete and the design passed their maximum repeatability, you will see not repeatable behaviour/performance. Paces will slow down, reps will likely look a bit different, rest intervals will likely increase within the set, but they will be suffering greatly. This doesn’t make it bad, you just wanna be sure the individual knows why they’re going through that.

All of this does depends on the ability of the athlete. A novice, versus intermediate, versus advanced, versus elite.

Number 2 – Design Strategies

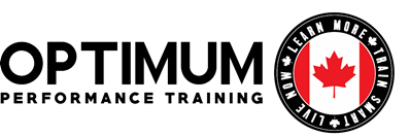

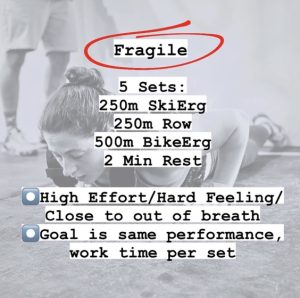

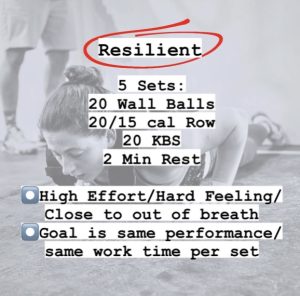

Fragile ▶️ Resilient ▶️ Anti-Fragile

(Novice▶️Intermediate▶️Advanced)

Now let’s discuss modality selection and inclusion for work set designs with the intention of promoting repeatability for various levels of individual ability.

Overall, we are trying to select and order modalities based on their inherent nature, being ones in which there is a large range of intensity possibility (ranging from sustainable to unsustainable – i.e. Rowing) versus ones in which the intensity range is fixed (unsustainable intensity only – i.e. Chest to Bar Pull-ups).

Further, they’re also has to be a consideration of which muscle groups the unsustainable movements will be imposed on. This has consideration with regards to the individual ability and the challenge you are trying to impose on them.

⏺️Fragility

Broadly speaking, this would be individuals of relatively low training age and relatively low fitness. As you can see, the modalities selected in this Work:Rest design are meant to promote repeatability. Now, that doesn’t mean the individual can’t screw it up, but if the wording and language and details are done correctly, they should get it right. Emphasize starting slow with these people. If they end up getting faster every set, that’s not a bad thing.

⏺️Resilience

Individuals in this stage, that being intermediate, can and should still use designs from slide 1, but should also use designs from slide 2. In this very basic example, we are simply alternating between large range intensity modalities (potentially sustainable) with fixed intensity modalities (unsustainable).

⏺️Anti-Fragility

Individuals in this stage, Advanced to Elite, can and should still use designs from Slide 1 and Slide 2. However, individuals in this stage will benefit from being challenged in a specific way. By stacking fixed intensity modalities on top of one another with the explicit purpose of challenging their repeatability. This can be done, and has been done by others, in many many ways.

Number 3 – Work:Rest

Another important consideration with regards to considering repeatability in your designs is manipulating the work and rest durations.

As a general rule, you will want to start beginners out shorter in terms of work intervals, and generally match the rest time to the work interval. For example, 30 seconds on, 30 seconds off. This is especially true when using unsustainable modalities in the design (ie – wall balls, thrusters, db snatches, weight lunges, etc).

For advanced and elite level individuals, short intervals (ie 30 sec) may work for specific movements or scenarios (think EMOM or Skill Work), but for developing and improving work capacity, they are not going to be your best option.

One of my favourite researchers, Philip Skiba, puts it pretty succinctly. “30 second intervals feel easier because they are easier”. He means, physiologically, they are much easier to perform and to recover from than longer intervals of the same work intensity.

In this context… if there is little chance of failing, there is little chance of gaining.

When giving longer work bouts, for example, 2 to 8 minute repeated bouts of work for higher level individuals, I would recommend a work to rest ratio of 1:1 to 4-5:1. Meaning, you may prescribe work intervals of 8 minutes of work, followed by 2 minutes of rest. You could do this with beginner level individuals, but you would have to frame the work as being easy or, moderate at most. You can’t ask these people to work hard and then only have a short period of rest before going again. Well, you can but you’re just going to make them suffer for little benefit – “too much pain for too little gain” (Stephen Seiler).

The reason I like doing this is because when the experienced individual knows there is only a short rest period, they should (emphasis on should) reduce their effort and get closer to repeatability in terms of their pace.

Your max repeatable pace for 5 minutes of work, followed by five minutes of rest is not the same as 5 minutes of work, followed by 1 minute of rest.

When it comes to a competition event, implementing the proper work rest periods will lead to the best outcome.

For example, I watched an individual performed this test in our gym:

20 Min AMRAP:

5 Strict Chest to Bar

10 Push-ups

15 Air Squats

Previously, their instinct is to go unbroken as long as they can into the 20 minutes. Which, only ends up working for a few rounds. Now, with the benefit of experience, and some coaching, the began performing the event in a very specific and strategic manner.

Perform the pull-ups as 3+2 every round, push-ups as 6+4 every round and 15 relaxed squats. For this person, the crux of the event was the strict chest to bar, as it is for most.

Knowing the event is 20 minutes in duration and understanding that the last 5 minutes count just as much as the first 5 minutes, allows you to anticipate what is to come and pace according to that. Thankfully, the strategy worked out well, and they ended up achieving effectively the exact same pace per round for the entire 20 minutes, with their last minute of work being the fastest work of the entire test.

When planning performance strategies like this, you need to balance the individuals ability to perform the work bouts, their ability to recover from and between the work bouts, and their willingness to try.

Again, and I will emphasize one last time, they were able to make this 20 minutes of work repeatable from round to round. However, repeatability is not sustainability, and they should not be confused with one another.

The main thing to consider with regards to promoting repeatability, is achieving the correct pacing in a typically unsustainable environment (ie CrossFit).

For many individuals, getting this pacing right will come naturally. For many other individuals, it will not come naturally, and it will feel hard to get right. They may second-guess themselves, and they will continue to get it wrong even though they are trying to get it right. For individuals like this there needs to be explicit challenge for “pacing“ in the training designs every week.

Achieving the correct pacing for the beginner is mainly in the hands of the coach to provide them the opportunity to display repeatable bouts of work. You the coach are prescribing the work, you have a big part to play in this. Keep it really simple and doable at the start and just slowly build from there.

On the other end of the spectrum, those wishing to compete at the highest level in CrossFit, the responsibility is really on them to get it right, with feedback and communication as needed from the Coach. Helicopter coaching will not help these individuals. They need to learn to know themselves. And that comes from repeated trial and error.

–Michael